KINGSTOWN, St. Vincent – Four Vincentian historians who were commissioned by the government to write the history of the country have presented the manuscript of the first volume, which documents the country’s history through 1838, the end of slavery.

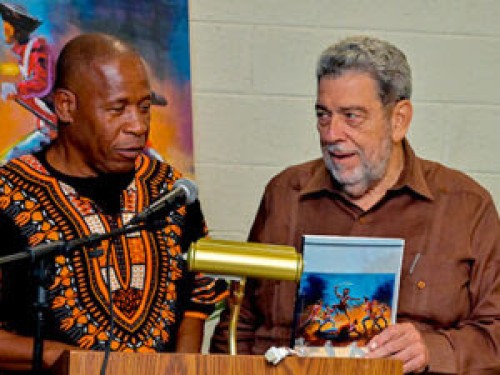

The historians – Adrian Fraser, Michael Dennie, Arnold Thomas, and Cleve Scott, presented the document to Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves earlier this week.

The historians – Adrian Fraser, Michael Dennie, Arnold Thomas, and Cleve Scott, presented the document to Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves earlier this week.

The government says the manuscript will be published and available to the public by October 27, the country’s 46th anniversary of independence from Britain.

Speaking at the presentation ceremony, Scott said in the introduction of the book, the historians “pay homage to the work and support of the government for bringing us together”.

He noted that the historians, all of whom are from different generations, have met for three to four hours twice a week over the last few years.

“So in the introduction, we start with geography,” he said, adding that it includes the size of the country and the number of rivers.

“And from that, we move to discuss the importance of history,” he said, adding that the “epithet” on the first page says, “If you want to enable a nation, show its history.”

“And we move on to explain that it is unfortunate that after so many years, we did not have a national history,” Scott said.

He said the historians then went through the various speeches by Gonsalves, “to show that even before becoming prime minister, he understood the importance of history. And it was no surprise to us that his government invested in this undertaking”.

Scott said the historians went on to explain that one of the highest forms of history is the memoir.

“And we are fortunate to have a past prime minister in Sir James Mitchell and the current prime minister, in ‘The Making of the Comrade’, giving us this historical biography.

“And we go on to explain that in writing this history, we are correcting a lot of things that are incorrect.”

He said that throughout volume 1, the reader will find examples of “real flesh and blood people”.

“So the emphasis is not on statistics and descriptive things. It’s about telling the story of real people,” Scott said, adding that, for example, it includes the example of Nelly Ibo, an enslaved woman in Mayreau who killed a planter.

“We speak about women also in Fair Hall … where they attempted to burn down Fair Hall estate for over 50 years,” he said, adding that the attempts to torch the estates continue in volume 2 of the book.

Scott said that the historians had to draw on a feminist to try to understand why the women were so intent on burning that estate.

Scott said that the book refers to the First and Second War for Sovereignty rather than the First and Second Carib War.

Scott said in the introduction the historians “set up the scenario. We explain things that make St. Vincent very special.”

He said that after much debate, the team agreed on Kevin Lyttle’s “Turn Me On”, released in 2003, and the nation’s election to a temporary seat on the United Nations Security Council from 2019 to 2021.

“For us, those two are the most significant things that have brought St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and continue to bring St. Vincent and the Grenadines global recognition.”

He said the introduction also documents some of the unique things about SVG, including that it is the only place in the world where people say “bottom foot” rather than “foot bottom” to refer to the soles of the feet.

“And we explain a lot of things. For example, what we call goat cook, it was called a marooning picnic. … And the introduction essentially sets out to make you feel proud as a Vincentian, to carry a Vincentian passport in your pocket,” Scott said, adding that unlike his children, he only has a Vincentian passport.

Meanwhile, Dennie said in writing the first volume, the historians wanted the readers to have “a sense of astonishment”.

“Think of here we have in the year 1508, Calinago leaving St. Vincent, travelling almost 1,000 miles, heading towards the Bahamas, heading towards Puerto Rico, to fight against the Spanish,” Dennie said.

“At the very beginning of the fight against colonial invasion of the Caribbean, the Vincentians were there, and when the fight ended in 1796, St. Vincent was the last battlefield. We fought for 300 years. That is astonishing,” he said.

“We need to also have a sense of reverence, because with one comes the other. This fight means that whereas in places like Jamaica, … Puerto Rico, … The Bahamas and elsewhere, you have the genocidal impact of colonial presence. Vincentians delayed the genocide; we fought them off, held them off for a long time,” Dennie said.

Thomas said that the first volume also documents chattel slavery — 1797 to 1834.

“The history of sugar and African enslavement in St Vincent and the Grenadines is remarkably different from that of most Caribbean territories,” Thomas said, adding that the territory served as a refuge for fugitives from slavery from Barbados for more than 100 years.

“Barbados, of course, is the single most important island in the history of plantation slavery for a simple reason: it was in Barbados that British planters first combined the availability of large areas of land, the labour power of enslaved Africans, the technological capabilities of the sugar factory and Dutch capital to produce the plantation economy and slave society.”

He said that by 1725, plantation slavery had become the dominant mode of production throughout the British colonies in the Caribbean and in North America, except in SVG.

Fraser said that as a high school student, he was exposed to British and European history, and, therefore, knew a lot about the number of wives that Henry VIII had, which meant very little to him.

“When I first went to university and I checked the libraries, I realised how much was written about the West Indies and even about St. Vincent,” Fraser said.

He detailed how emancipation of slaves materialised in St Vincent after the law was passed in England, including the forms of resistance that people put up during the period of apprenticeship between the passage of the law and the actual emancipation.

“… the major form of resistance was the burning of fires,” Fraser said, adding that on occasions, the coloniser could not find out who lit the fires and everybody had to bear responsibility for it.

Fraser said that the historians are now moving to volume 2 of the country’s history, which begins with the freed people trying to fashion a life of their own.

“… we’ll find that in about 10 or 15 years after emancipation, quite a number of villages throughout St. Vincent and the Grenadines were established, so that the development of the country owes a lot to these enslaved people,” Fraser said.

He said the middle class came later on.

“… so Volume 2 is going to be interesting, and it’s going to be showing how Vincentians who came out of a period of enslavement were able to fashion a life of their own and able to build a St. Vincent,” he said.